I never implied anything about the US.

Avid Amoeba

- 11 Posts

- 1.33K Comments

So not trolling, alright. Sounds to me like you consider them competent in what they did well while not subtracting what they didn’t. Let me contrast the Russian government with something that to me looks much more competent - the Chinese government.

1·2 days ago

1·2 days agoThey just keep running into faces.

You call competent a government that pulled the “special military operation” and led hundreds of thousands of its people into death for not much of anything? You must be trolling.

371·2 days ago

371·2 days agoOK, so people can use the definition instead. In fact it might be more useful.

23·3 days ago

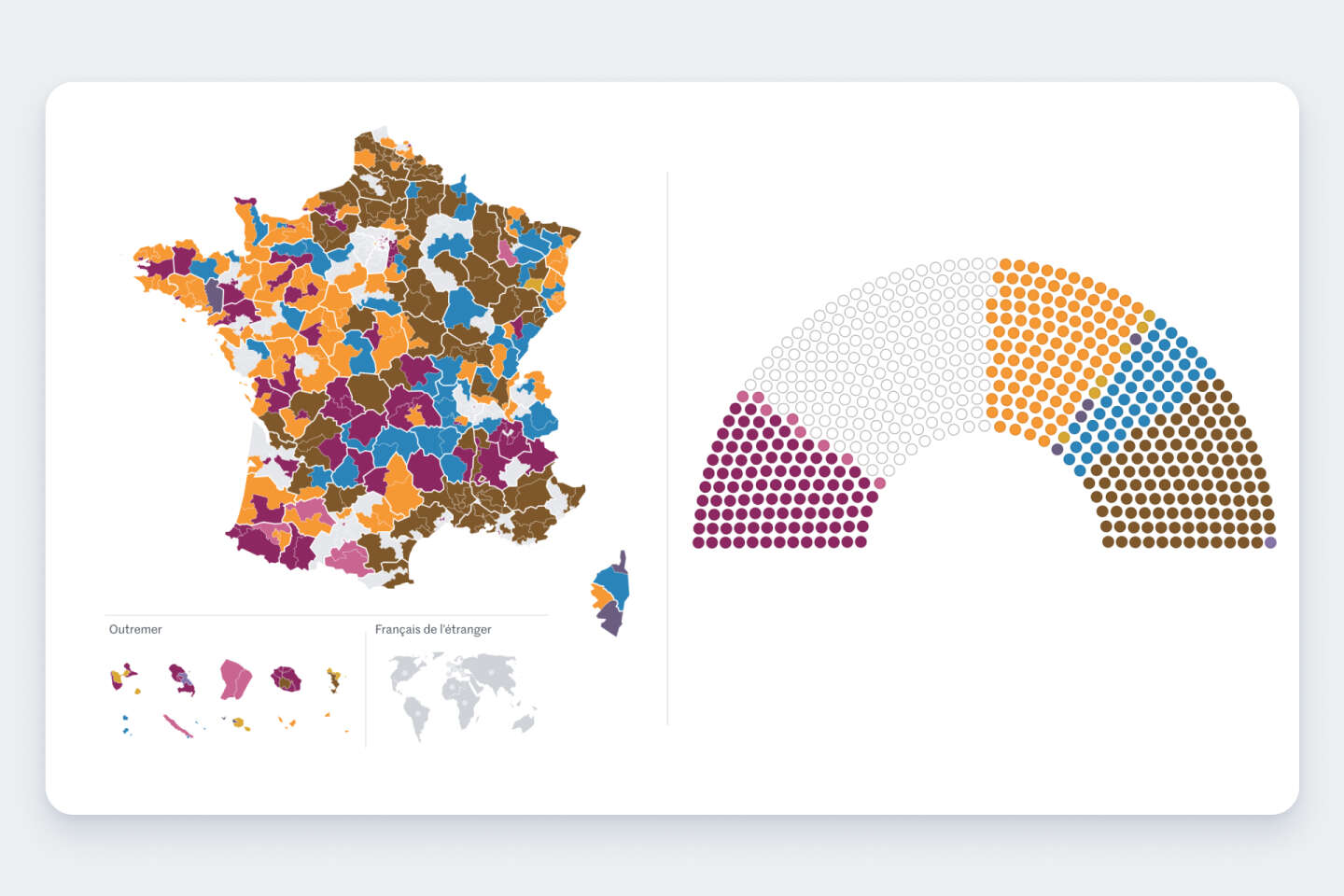

23·3 days agoThis is beautiful! It’s like a textbook example for everyone paying attention to draw crisp conclusions for how the system works.

43·3 days ago

43·3 days agoLMAO

755·3 days ago

755·3 days agoHonestly I don’t know what’s up with the mass delusion about Bluesky being oligarch-free. It’s understandable that most don’t know or haven’t looked into it, but then some folks that should know better are displaying the same ignorance.

3·3 days ago

3·3 days agoYup, from the first availability till today, no shenanigans.

1·3 days ago

1·3 days agoDon’t discount the other autos lobbyists. Some have invested heavily in new factories being built and have many more workers in the US combined. Not to mention they can keep selling gas guzzlers till we burn the planet.

134·3 days ago

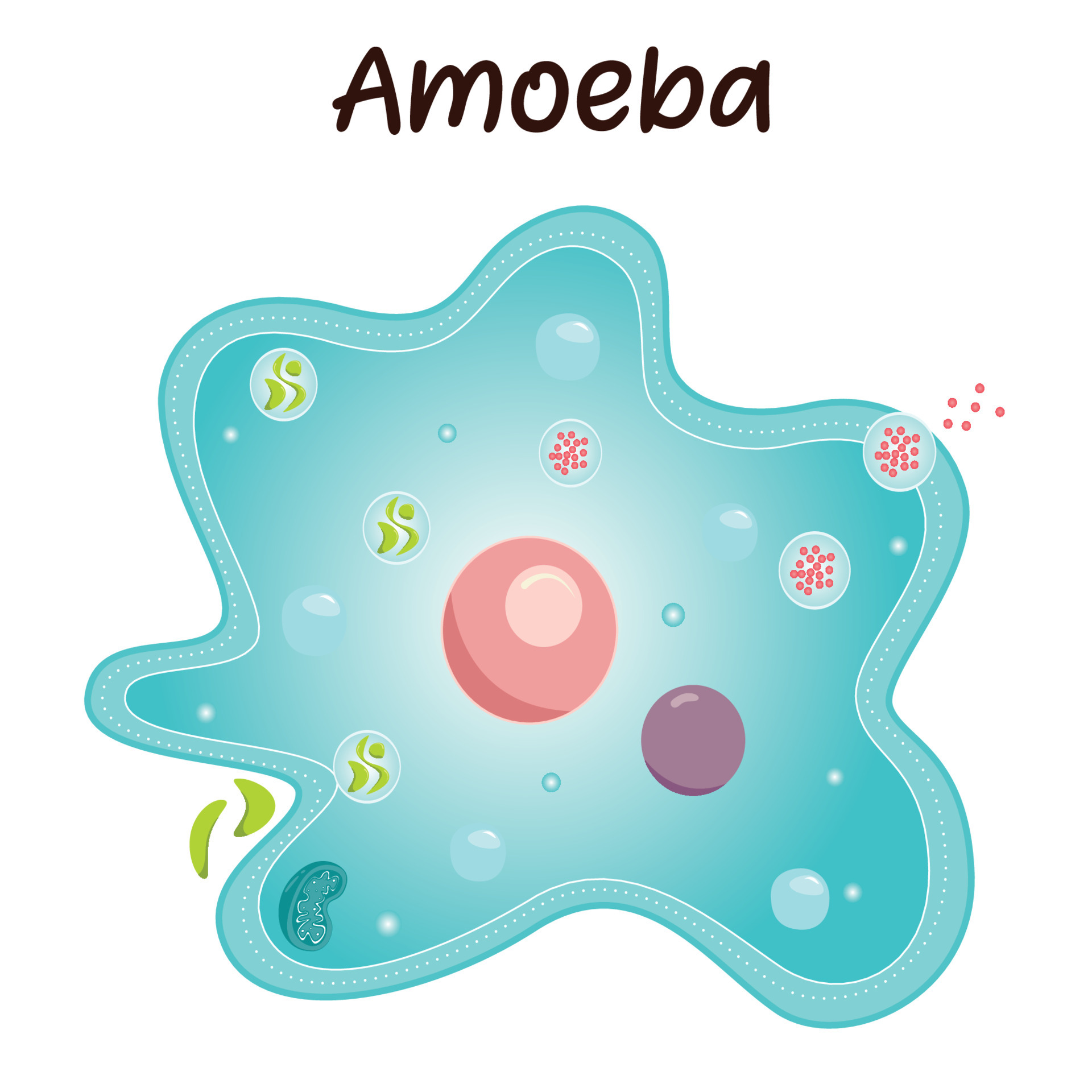

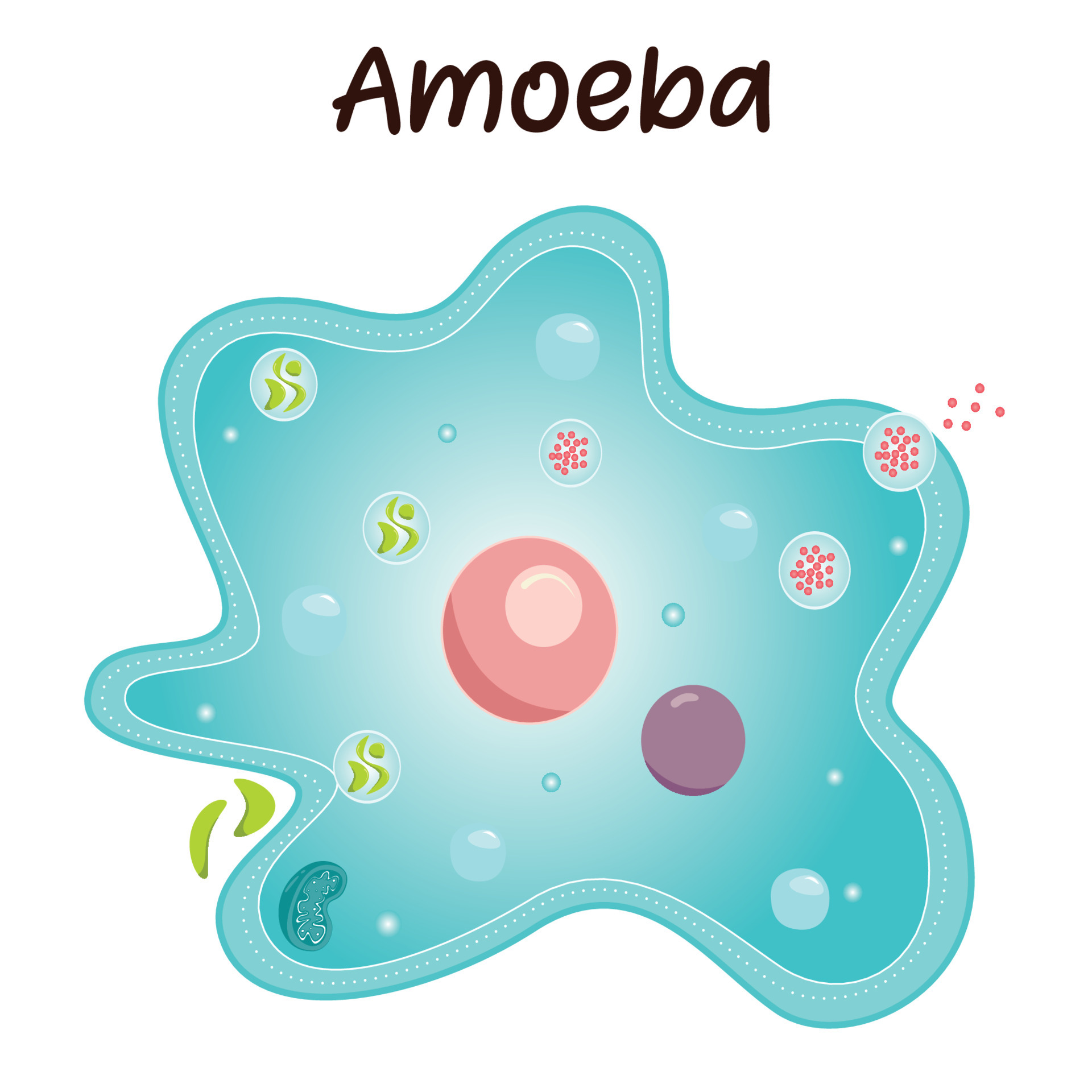

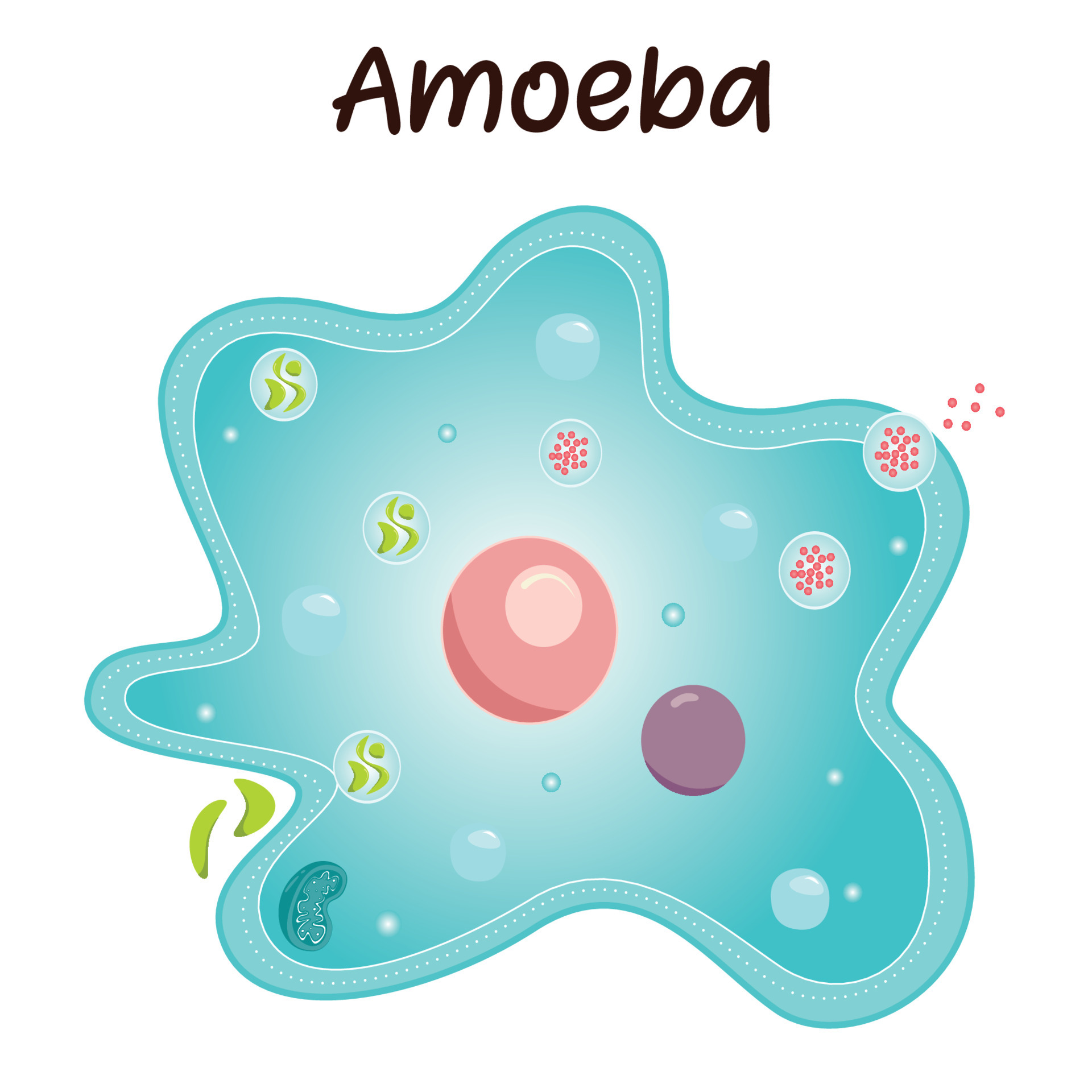

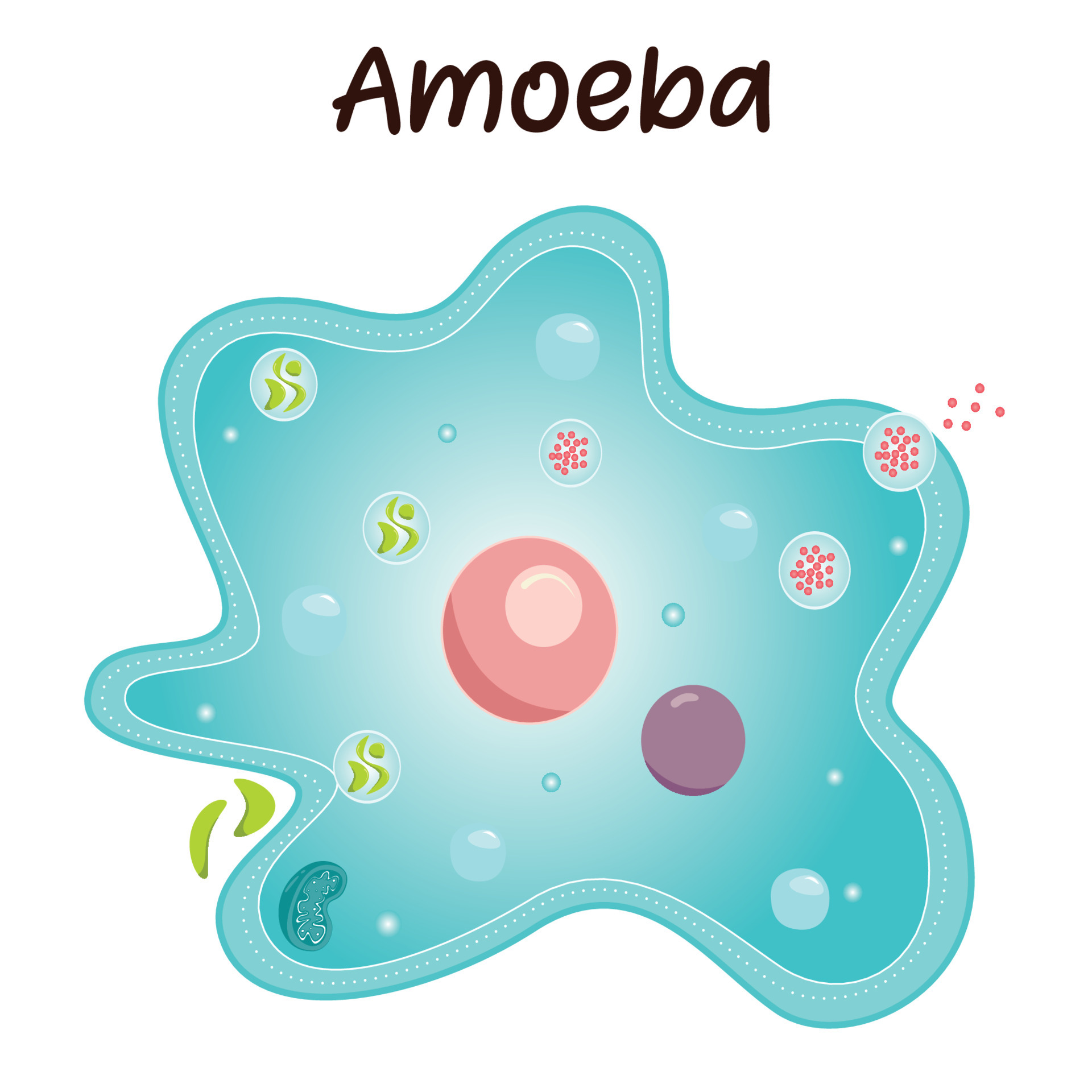

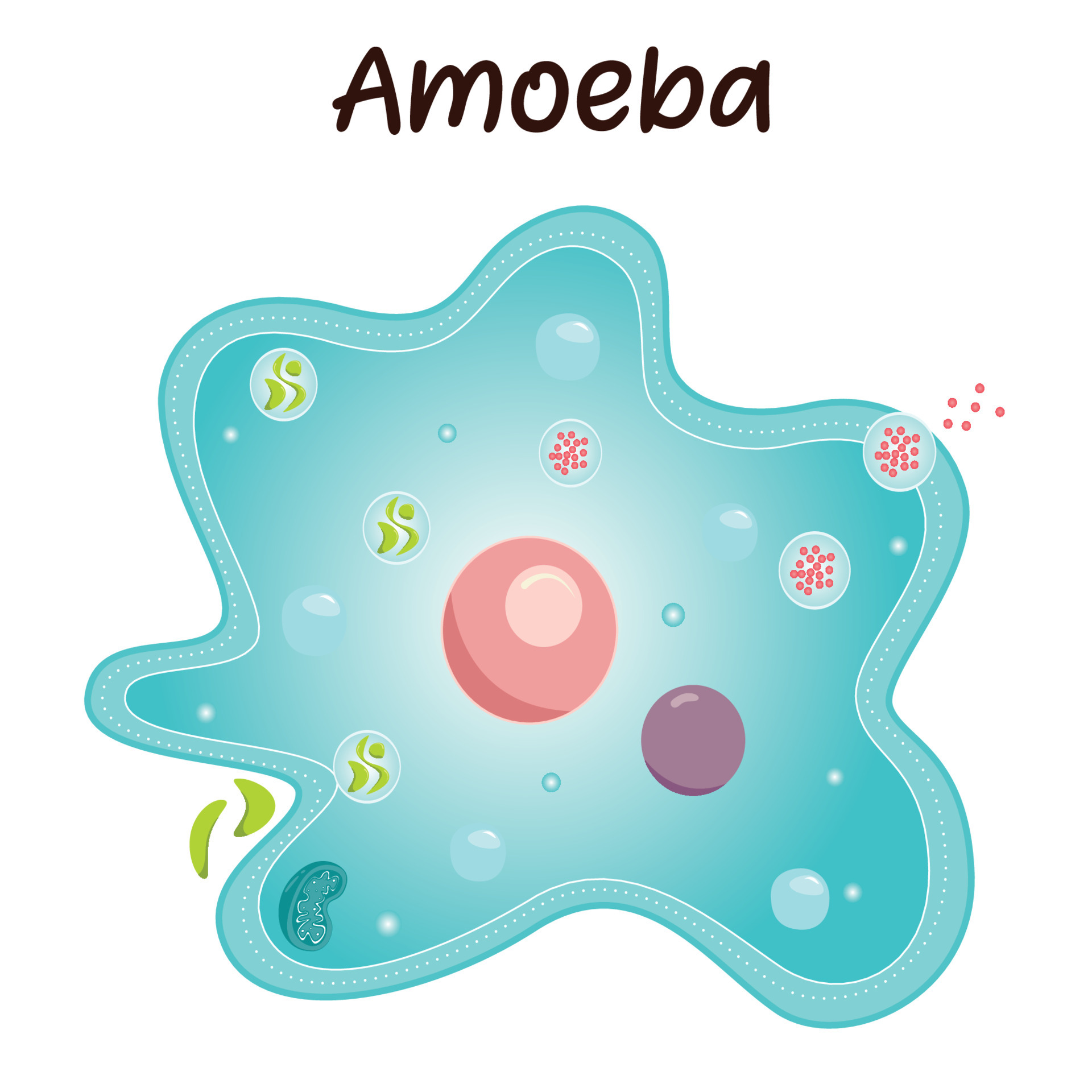

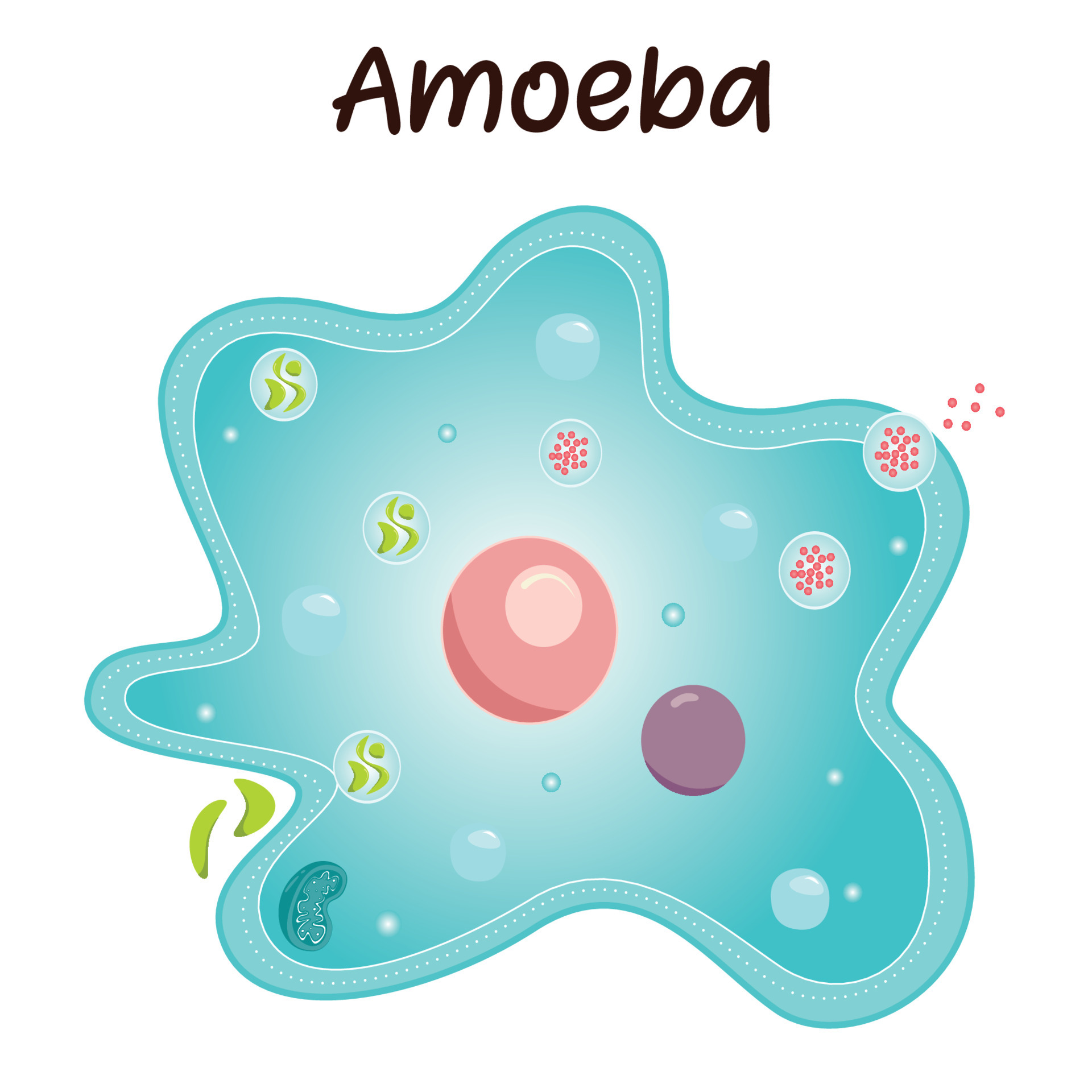

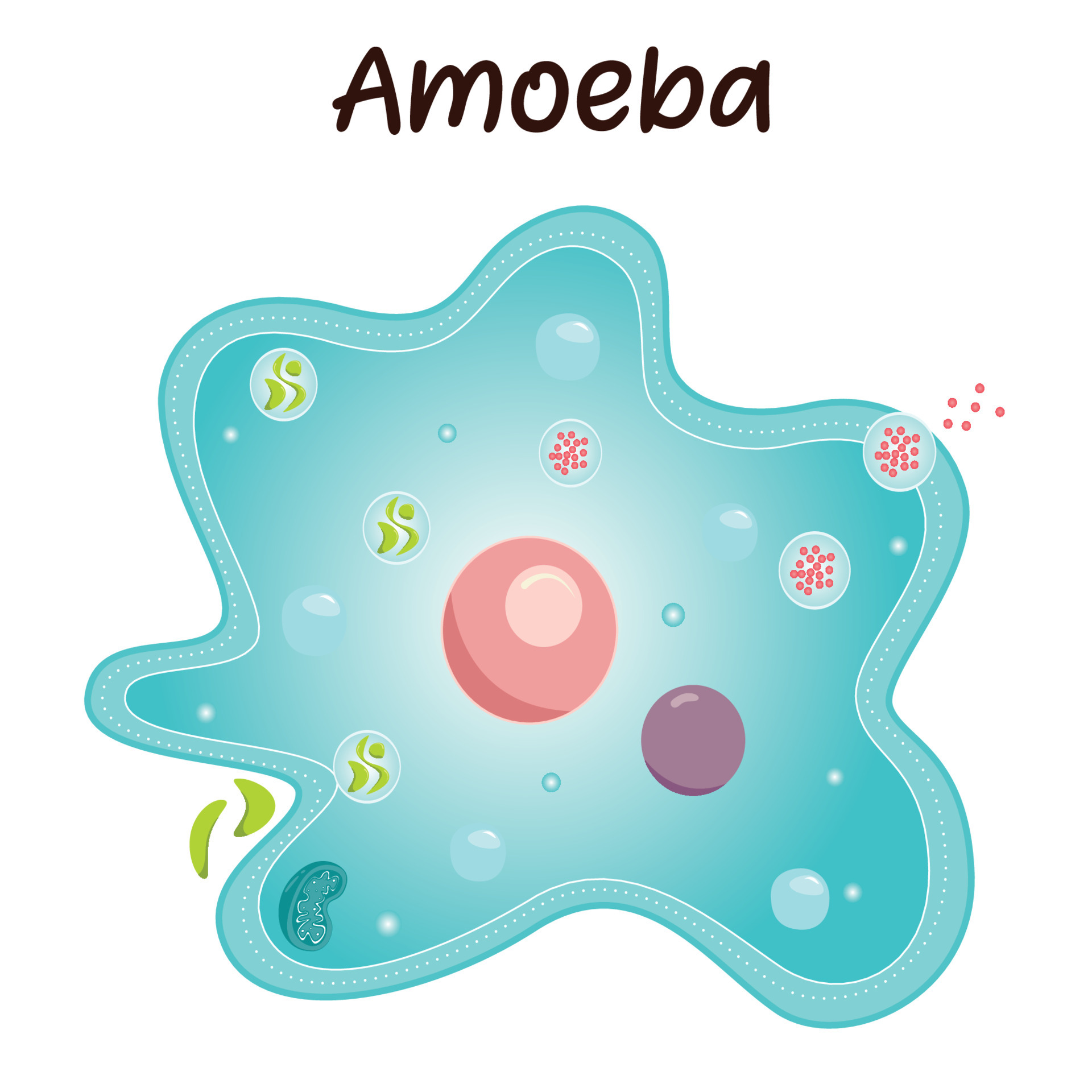

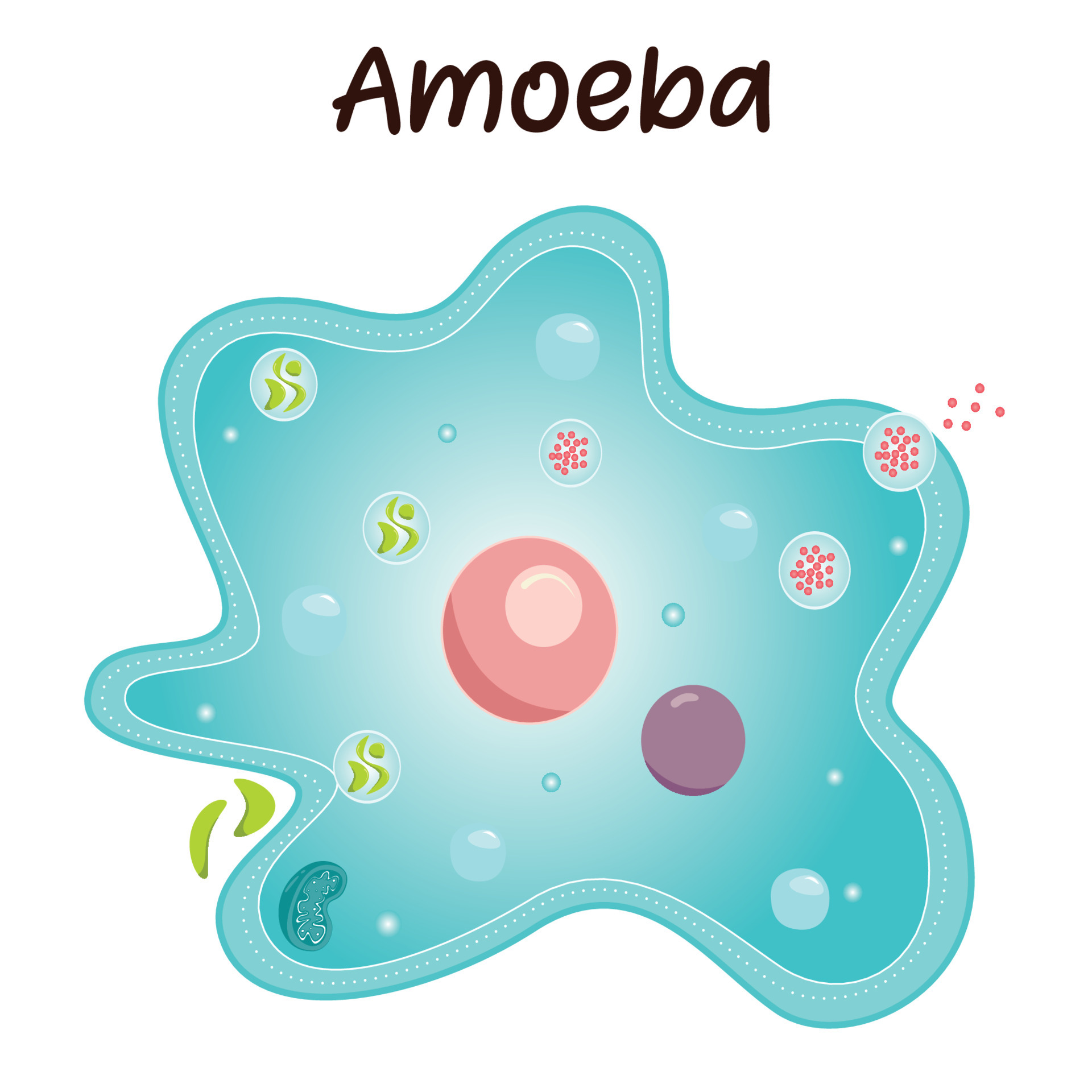

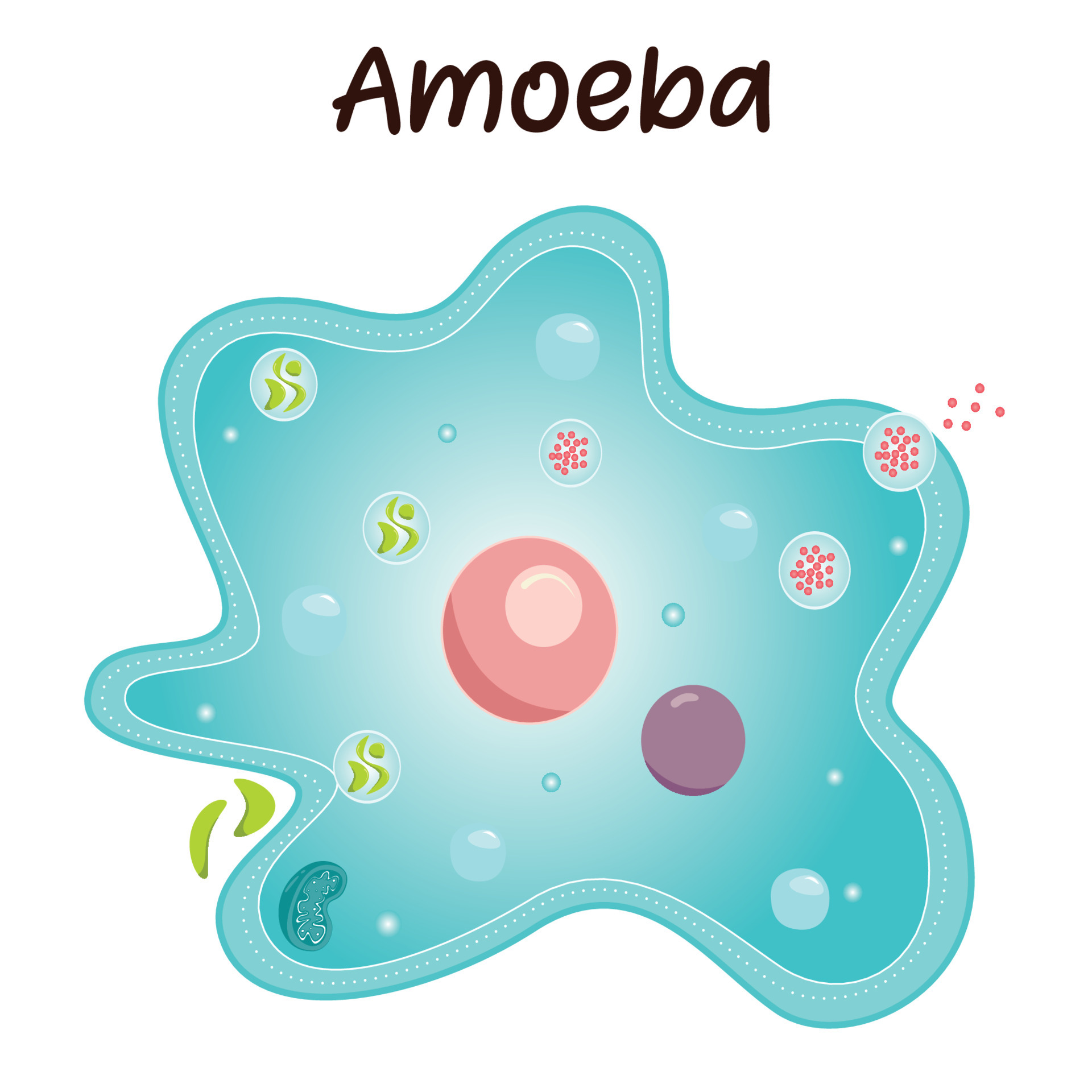

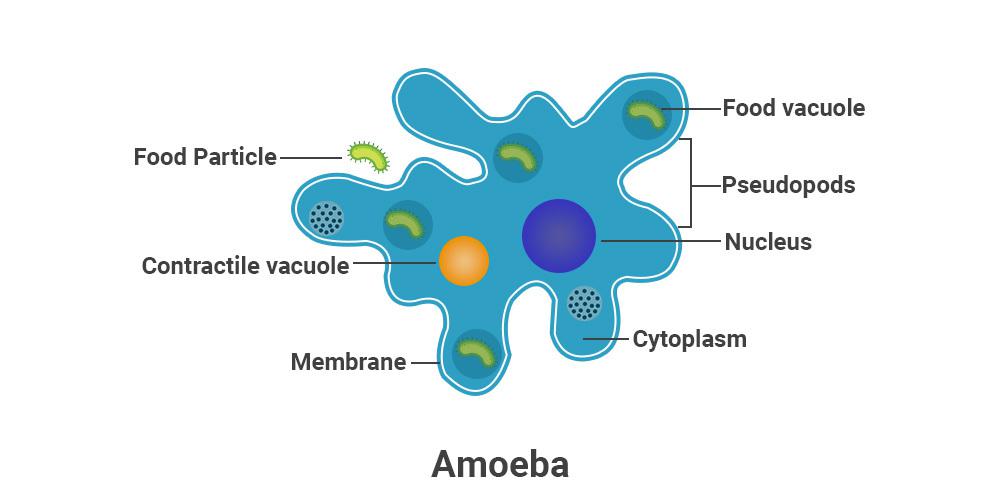

134·3 days agoVisual aid

21·4 days ago

21·4 days agoI’m trying not to accelerationist but this clown car is getting pretty fast.

Every time I hear a junior developer say we should rewrite something they have made 0.1 effort understanding, I thank the JS world for not giving a generation or two of developers a well thought out application development framework.

You lost me at shitting on legacy code. My brother in Tux, we don’t rewrite code willy-nilly in the FOSS world either and for a good reason. New code always means new bugs. A shit ton of the underlying code in your Linux OS was written one or more decades ago.

85·4 days ago

85·4 days agoThis is because employees in South Korea can “only” work a maximum of 52 hours per week, including twelve hours of overtime. As a result, employees often have to leave work and go home even when important tasks have not yet been completed. For this reason, key employees of the Exynos team are reported to have worked unpaid overtime more and more frequently over the past few years, with the extra hours going unrecorded.

Why is SK’s birth rate in the shitter.

9·4 days ago

9·4 days agoWe’ll know if we hear any Big Ag name being raided.

4·4 days ago

4·4 days agoGiven everything we’ve seen over theast little while, including the process of non-profits getting taken over by their VC funded subsidiaries; that difference you see is almost certainly a matter of being at a different point in their respective profit timelines.

1·5 days ago

1·5 days agoSo you’re telling me there’s a chance?

Today they’re smashing it at the rate of installation per year.